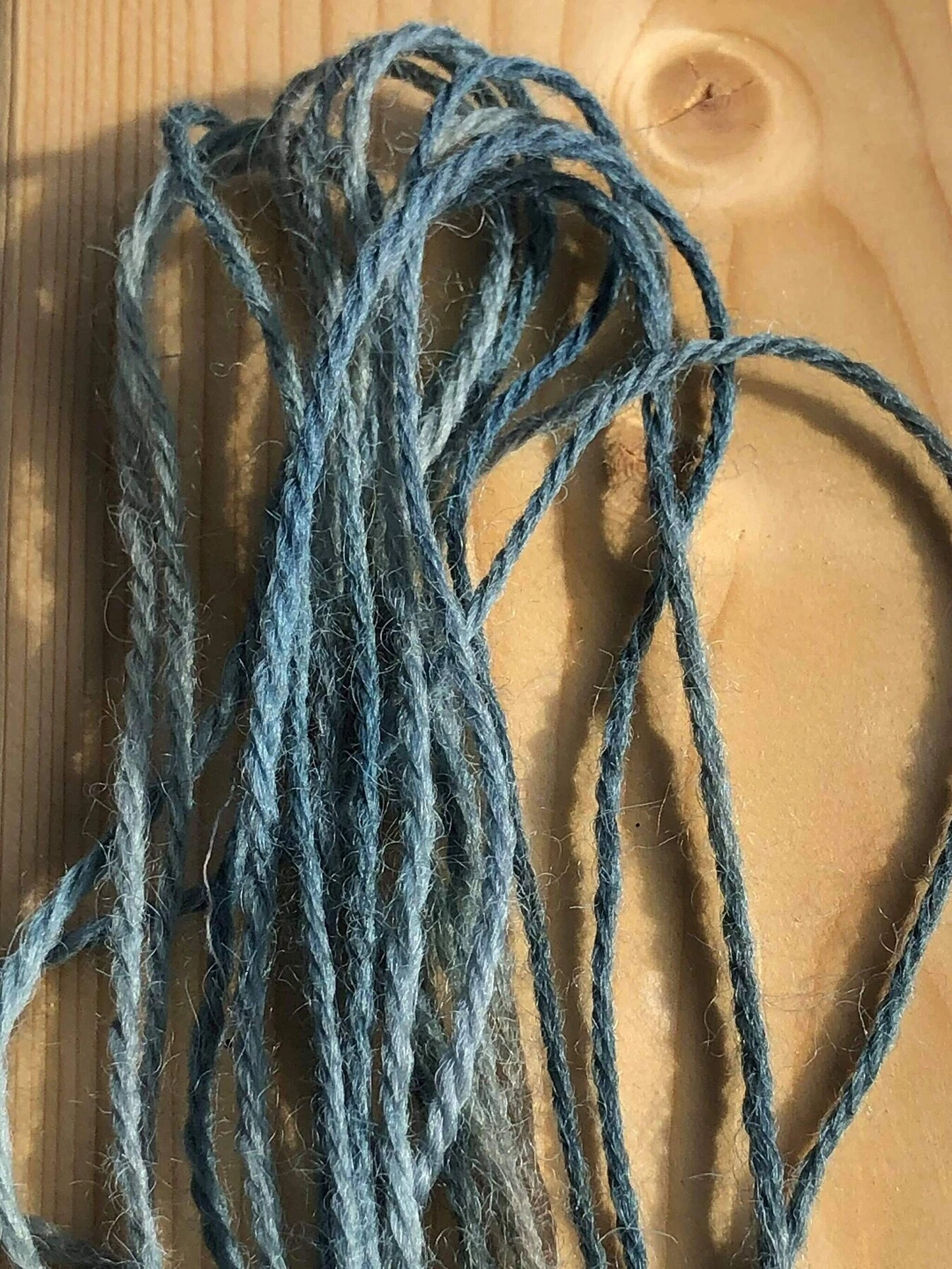

The most common colour in Estonia during the early mediaeval era, according to textile discoveries, was “blackish-blue.” According to Riina Rammo, an archaeologist at the University of Tartu, the dark-purple shade was added to the blue hue by combining native flora, whilst the blue colour was produced by using imported compounds.

In Estonia, female burial sites are where the majority of mediaeval attire has been discovered. Their clothing had complex metal ornamentation that preserved the fabric in the ground. The trendy colour of the time, according to Riina Rammo, an associate professor of archaeology at the University of Tartu, was unquestionably blackish-blue.

“From the eleventh through the fifteenth centuries, we have knowledge on the fabrics used in the Estonian region. I’m not sure if it’s still in style now, but back then it was unquestionably the most popular colour for Christmas celebrations, especially for women,” she remarked.

She has finished a preliminary investigation of the process used to produce this blue hue with help from her Finnish colleagues Krista Wright and Mervi Pasanen. The fabric’s blue colour is a result of indigotin-based dyes. One of the earliest colours used by humans, organic indigo is a powder made from the leaves of the indigo plant Indigofera tinctoria. The only natural blue is it. However, it wasn’t until the 17th century that it made it to Estonia.

The Mysteries of Medieval Woad Trade and Dyeing in Estonia

Rammo claims that indigo originated in this region during the early Middle Ages from the woad (Isatis tinctoria L.), a member of the mustard family, to which local plants were added in northern Estonia and southern Finland, respectively.

The woad (Isatis tinctoria), a biennial plant with yellow blooms that flourishes now in Estonia’s coastal regions and islands, is about a metre tall. “It’s not what we would call a native plant, which would have been growing wild here since the Ice Age, but it has been introduced, probably as a weed,” Rammo says. According to the archaeologist Jüri Peets, it may have come to this area in connection with the Middle Ages or subsequent commerce renaissance.

“We have no ethnographic reports indicating that the woad that grows naturally here was used for dyeing,” Rammo stated. It is known that the plant began to be widely farmed in Europe from the 13th century onwards before being imported to Estonian territory in a semi-manufactured form. It was made into pellets and after drying, cutting into pieces, and fermenting, it was put back together. The completed item served as the base for a dye solution.

“There are images from the Middle Ages of merchants carrying a bag of woad balls. Although more extensively distributed from the 13th century onward, recipes and textual sources on the trade have also survived, according to the assistant professor. She claims that it is unclear exactly how and where trade in blue dye occurred in Estonia in the 11th and 12th centuries.

While archaeologists were well aware of the use of woad, it was a surprise to find that in northern Estonia and southern Finland, additional dyes had been mixed in with the alien pigment. “Either different dye mixtures were made, where the textile was dyed in succession, or several substances were combined in one dye solution,” said the co-professor.

It is still unclear which colours were added to the woad because just a preliminary examination has been done. Rammo stated that her team’s current conjecture is that Lasallia pustulata, a local species of lichen, may have been the culprit. “This lichen can produce somewhat reddish and bluish purple tones. It can add a darker tint when used with a woad, she explained. It should be mentioned that the lichen is protected in Estonia and cannot be taken.

The aim in the past, meanwhile, might have been to create the darkest hue imaginable. “Woad blue was the era’s most durable textile colour. The co-professor said that it persisted on the fabric, didn’t wash off, and wasn’t concerned about fading. Additionally, the blue colour may have appeared more prestigious to the user due to the fact that the dye’s primary component had to be imported from afar.

Estonia’s Ancient Dye Enigma

The study is only the first stage of the larger, internationally funded “Colour4CRAFTS” initiative, which combines scientific disciplines with cutting-edge product creation. “The aim is to develop, in cooperation with companies and textile chemists, new dyeing technologies that would be applicable today, but at the same time sustainable,” Rammo stated. For instance, new techniques might consume a lot less water than those already in use.

According to the co-professor, the textile heritage of the Baltic Sea’s eastern coast offers ideas and fresh resources for developing new technologies. Compared to central Europe, the natural dye supplies used here are slightly different. “It is lichens and tree bark that provide inspiration for chemists developing new dyes in laboratories that can be applied using these water-free methods,” Rammo said.

She and her coworkers will test vintage recipes as part of the research and compile a sample collection for use as a resource. “Comparing the results of analyses of today’s samples with those of the past should tell us what was used to dye the textiles.” The issue, she claimed, is that Estonian native flora may not be included in European reference collections and have so remained unrecognised. “That’s why it’s so exciting that we can focus on a specific region and the colour plants found here,” she continued.

In Estonia, the image is not entirely uniform. Early mediaeval northern Estonia’s textile industry shares a lot of technological characteristics with southwest and southern Finland. However, the mediaeval Siksälä region in southern Estonia’s southeast stands out for having a particular textile culture that is comparable to that of the Latvian region. Evidently, woad was the only substance utilised there. Once more, this is a highly intriguing difference that has to be researched, according to Rammo.

She is also curious about the other colours that were utilised in Estonia at the end of the Middle Ages in addition to blue. She wonders, for instance, why there aren’t more yellow-colored clothes worn here because “I got the impression that yellow was not used very much in our region – it wasn’t a colour that have been appreciated.” She claimed that because of how poorly the yellows and browns are retained in the soil, her impression of preservation might not be accurate.

“Cultural ideas influence both how colours are utilised and how they are perceived. For instance, we cannot immediately apply insights made in Denmark to the Estonian setting. Rammo continued, “I still want to see the chemical evidence of what was used here.

In the collection “Interdisciplinary Approaches to Research of North and Central European Archaeological Textiles,” Riina Rammo and colleagues wrote about their research. The North European Symposium for Archaeological Textiles Proceedings.